Why do existing elites support dictators? What drives journalists, jurists, academics, bureaucrats, to agitate for authoritarianism, and then enable, operate and legitimise the illiberal one party state? It’s an old question, considered by Julien Brenda in his 1928 work La trahison des clercs., and now turned to by Anne Applebaum in Twilight of Democracy. In doing so, Applebaum has perhaps unintentionally written an excellent illustration of Peter Turchin’s concept of ‘elite overproduction’ by writing a series of portraits on modern counter-elites. Examining why will be the focus of this piece.

It’s a good book, supremely readable, compact and insightful, even if it never quite outgrows the series of essays on which the book was based. This began with a long read on polarisation in Poland in 2018, and pretty much includes every essay Applebaum has written since, including an examination of the appeal of Russia to American conservatives, an exploration of an international nationalist convention, a meditation on the implications of Brexit for the Conservative Party, and an in depth portrait of Laura Ingram’s shifting political views.

These essays form almost beat for beat the chapters of Twilight of Democracy, which begins in Poland, ducks to Hungary, travels to England, double backs through Spain and then Rome, crosses the Atlantic to consider the United States before finishing in France. This is no cohesive and systemic analysis of the causes of democratic backsliding and rising illiberal and anti-democratic nationalism - that ground is better covered by Democracy for Realists,How Democracies Die or the earlier works of Arendt or Popper.

Instead of focusing on systems, Twilight of Democracy is essentially a series of character studies, a narrative journey that examines the individuals behind the shift in democratic politics. Applebaum’s contribution to the conversation is her unique vantage point at the centre of the atlanticist anti-communist coalition as it existed in the 90s, and her front row seats to its subsequent disintegration across Europe and the United States in the past decade.

This perspective is vital, because it puts the focus squarely on the humans behind the headlines. Analyses of democratic dysfunction often get caught up in a sense of their own grandeur. They focus on grand statements of ideology, economics and human nature rather than anything as small as the motives of the individuals who actually bring it about. Looking too closely at the role of elites in democratic politics sits uncomfortably with the ‘folk theory of democracy’ as Achen and Bartels puts it, where voters, rather than party apparatchiks, media players and other political elites control the government, and so often political science has shied away from the subject.

But Applebaum cut her teeth as a historian documenting the gulags, not modeling the median voter theorem, and that experience serves her well in this book, which is unapologetically about the elite - namely the schism of the “right” as it had existed prior to 9/11. Of course the word ‘elite’ has been repeated so often in recent years as to lose all meaning, and Applebaum early on adopts a more precise term, the clercs of Julien Benda’s 1928 warning La trahison des clercs.

Clerc has been occasionally translated as ‘intellectual’ in particular a ‘fallen intellectual’ who enables totalitarianism, but Applebaum doubles down on Benda’s use of the term as ‘clerc in a medieval sense’. A clerc then is anyone who works to de-legitimise liberal democracies, and in their place legitimise authoritarian regimes. Many clercs are essayists, lawyers, judges, academics, novelists and other persons who would fit cleanly within the definition of ‘intellectual’, but a great many are not - conspiracy theorists, twitter trolls, data analysts, tech workers, advertising executives, partisan operatives, and talk back radio hosts. Applebaum makes clear that they are the central focus of the work - “This book is about this new generation of clercs and the new reality they are creating…”

This is both a far more useful and far more precise term than ‘elite’ which now means anything the author doesn’t like. To be a clerc is not to have a high prestige job, but to be an active and deliberate player in the game of politics, and Applebaum focuses on around five of them:

Jacek Kurski, director of Polish state television;

Mária Schmidt, director of the Terror Haza museum in Budapest.

Boris Johnson, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom,

Rafael Bardaji, former advisor to Spanish Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar, currently involved in the far-right populist party Vox.

Laura Ingraham, Fox News media personality.

And while Applebaum portrays each with varying levels of sympathy, there are two common threads in each:

None of these people are outsiders, all of them were either born into or were otherwise long established members of the political, cultural or media landscape as it had existed from the 80s-00s.

All of them found their position to be short of their ambition, and changed their politics in part to maintain, gain or return to power.

Applebaum’s portrait of Jacek Kurski here was telling:

A friend of them both told me she didn’t think Jacek had any real political philosophy at all. “Is he a conservative? I don’t think so, at least not in the strict definition of conservatism. He’s a person who wants to be on the top.” And from the late 1980s onward, that was where he aimed to be.

The sort of emotions that don’t usually get much attention from great political theorists played a big role in what happened next. Jacek Kurski is not a radically lonely conformist of the kind described by Hannah Arendt, and he does not incarnate the banality of evil. He has never said anything thoughtful or interesting on the subject of democracy, a political system that he neither supports nor denounces. He is not an ideologue or a true believer; he is a man who wants the power and fame that he feels that he has been unjustly denied…

But although he spent years in public life, Jacek did not win the popular acclaim that he thought that he, as a former teenage Solidarity activist, was entitled to.

The others on the list follow the same theme. Mária Schmidt, a scholar of communist and fascist regimes, who now vocally supports Orbán and is rewarded with state honours and influence. Boris Johnson, once mayor of europhilic London who leveraged his support of Brexit to climb from the backbench to Downing street. Rafael Bardaji,a Bush era neoconservative once central to Spain's decision to join the Iraq war in 2003 who reinvented himself as a Trump-esque populist to regain political relevance. Laura Ingraham, a former clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas who only got a prime time slot on Fox after aligning herself with Trump early on in the 2015 primaries and her politics shifted from Reaganite optimism to apocalyptic pessimism.

Applebaum identifies other factors as well, such as the fragmentation of the digital media landscape, the existence of a sizeable chunk of the population with an ‘authoritarian predisposition’ or the genuine ideological despair in Roger Scrunton’s England: An Elegy or the cultural declinism of Pat Buchanan. But if Twilight of Democracy has an underlying narrative, it’s of wannabe elites who wanted to be at the top, and leveraged illiberal populism to get there. It’s the single, unifying strand of the book’s many threads.

It’s impossible to read the Twilight of Democracy then without hearing the echoes of Peter Turchin.

Turchin and Elite Overproduction

2020 has been Peter Turchin’s year, with his theories exploding the popular consciousness, jumping from academic journals into TheAtlantic and The Economist. The reason? In 2010, Turchin predicted that the 2010-2020s would be one of increasing political instability and unrest, and the 2020s would be worse.

Of course the interesting part was how Turchin forecasted the growing instability (mathematics) and why he theorised this was happening: population immersieration (a glowing technical term for stagnating wages and decreasing quality of life), state fragility and elite overproduction. Or simply put, the idea that there were too many qualified, educated, capable aspiring elites than there were positions for them. As Turchin put it:

The supply of power positions in a society is relatively, or even absolutely, inelastic. For example, there are only 435 U.S. Representatives, 100 Senators, and one President. A great expansion in the numbers of elite aspirants means that increasingly large numbers of them are frustrated, and some of those, the more ambitious and ruthless ones, turn into counter-elites. In other words, masses of frustrated elite aspirants become breeding grounds for radical groups and revolutionary movements.

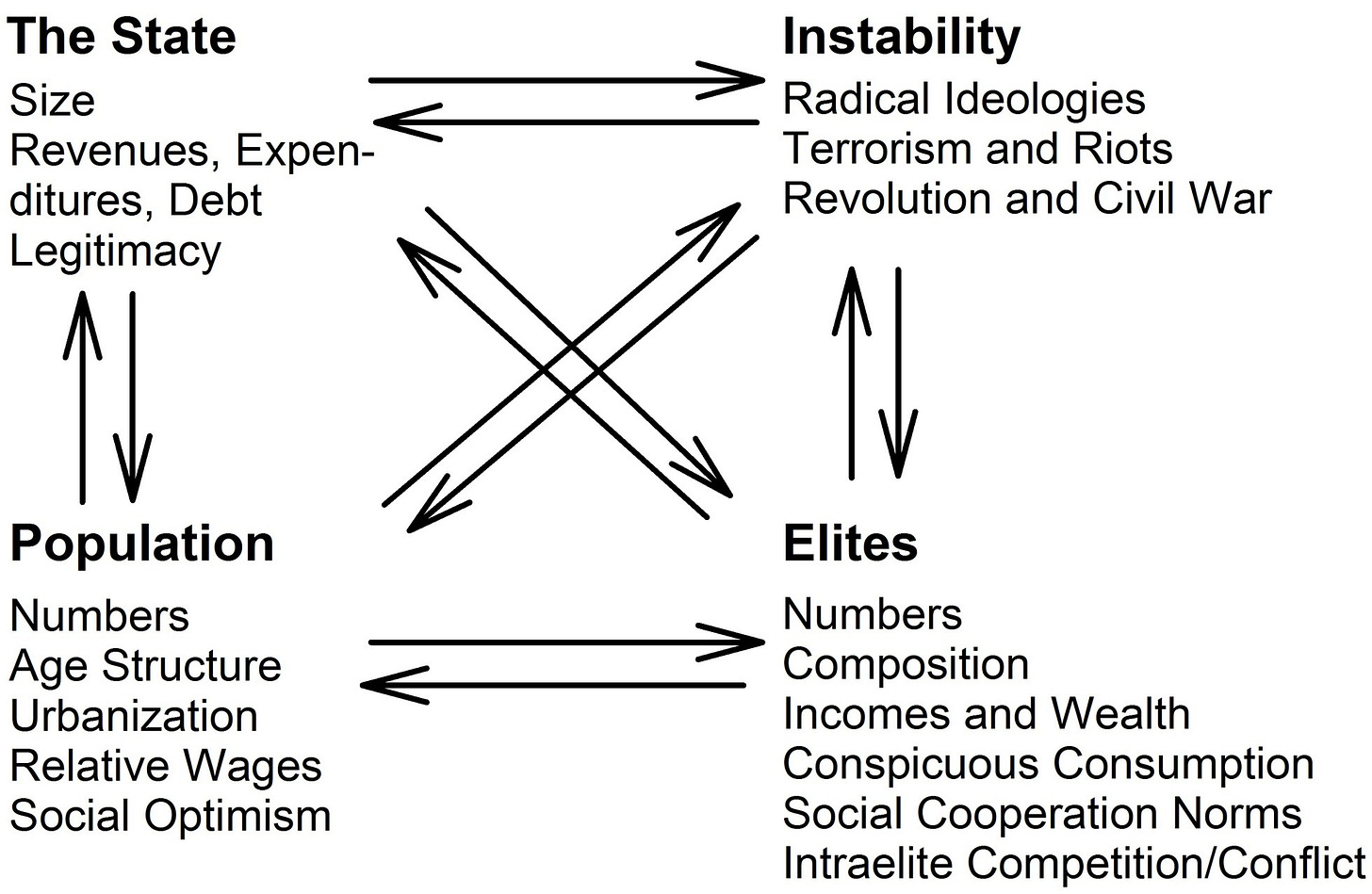

Turchin cut his teeth using mathematical models to predict the fate of pine beetle populations, and then from the mid noughties turned the same method to modelling the rise and fall of human civilisations. This study of what Turchin terms ‘cliodynamics’ produced structural-demographic theory (SDT). Where historians examined the micro, Turchin attempted to quantify the macro. (A very basic graphic representation of the factors of which is below)

A ‘counter-elite’ is of course a clerc by another name, aspiring elites who are unable to climb in the existing system, and who then attempt to change it. The similarities between Turkin’s descriptor of the causes of counter-elites and the motives of Applebaum’s polish clercs is striking:

Not everyone who was a dissident in the 1970s got to become a prime minister, or a best selling writer, or a respected public intellectual after 1989 - and for many this is a source of burning resentment. If you are someone who believes you deserve to rule, then your motivation is to attack the elite, pack the courts, and warp the press to achieve your ambitions is strong. Resentment, envy, and above all the belief that the “system is unfair” - not just to the country, but to you - these are important sentiments among the nativist ideologues of the Polish right, so much so that it is not easy to pick apart their personal and political motives.

Applebaum never mentions Turchin, or uses his terms, although it would be difficult to imagine that she is ignorant of him, especially given Graeme Wood’s portrait of his work in The Atlantic earlier this year. Regardless, Twilight of Democracy is essentially a character portrait of a series of counter elites or clercs- the humans behind Turchin’s mathematical models. For the past three years, the two of them have largely been writing on the same thing.

Twilight of Democracy is of course not the end of the road for Applebaum’s work on the subject, but rather a condition report for the world in 2020 for those of us living in it. It’s likely a prelude to a more substantial work to be published when the present begins to resolve itself into history. If and when that work is published it will be interesting to see how and if Applebaum addresses Turchin and SDT.

Chances are both of them will have a lot more to write about by then.